For absolutely not the first or last time I have been struggling with translation. The more it happens the more I ditch my ideas that I will never, ever try to get my brain around Old Irish and idly dream about maybe going back to college some day just to try to get a better handle on things. Not being a fluent speaker of my own language makes researching old Irish ..interesting.. but I am finding the more I really poke at it the more it’s making my brain sit up and take notice.

That probably is a weird opening for an article on a dyeing website. The reason for it is that I, as a member of the SCA, have chosen to concentrate on an Irish persona, and I really, really wanted to start seeing if I could pull some actual sources from existing texts. There aren’t that many, so far, in the same way that we are not blessed with many written sources anyway. What I’m going to write about in this post is a sort of exercise in trying to pin down how I tried researching this and why I am wading my way through sources from a relevant time period when I feel less than equipped to do so.

The mission: What colours did Irish people wear/dyestuffs did they use that we can be certain of in from actual Irish sources?

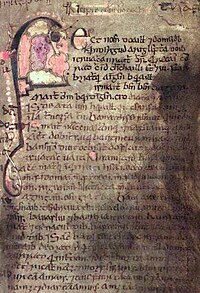

Anyone who has seen a Medieval Book of Hours knows that there is a very human tendency to present an idea, concept, or event using familiar images – historical biblical figures or Alexander the Great all find themselves depicted as white folk in medieval dress doing medieval things. I’m sure Noah and Moses wouldn’t know themselves. With the subject material I am about to discuss I was bogged down in a whole discussion about just how accurate you could treat the material as being before realising that it actually, for my purposes, it didn’t matter. I don’t care that the Roll of Kings is likely to have been rewritten by Christians to lever in a pile of lineage to take Ireland’s people back to the days of Noah, the fact that someone felt the need to do so is interesting in itself, but not to me right now. I, similarly, don’t care what actual colours they were wearing in 1640 BCE, I care what colours a later, medieval era writer felt were plausible in the 10th or 11th century in Ireland, and what that writer felt was important to talk about, which reveals that these are normal but somewhat noteworthy colours for that period.

I similarly got utterly bogged down because what I am going to speak about was something I found first credited to two different kings (Tighermas or Eochu Edgathach (Book of Leinster) and in other places just to Tighernas (Eochaid Úa Flainn’s ‘Éitset áes ecna aíbind’). That’s a matter of different sources, and again, doesn’t actually matter for what I’m trying to talk about, I really need to stop chasing rabbits down rabbit holes. But it does mean I got a strange sort of mild outrage reading one version as fact in, say ‘Traditional Dyestuffs in Ireland, an essay by Brid Mahon in Gold under the Furze. Studies in Folk Tradition Presented to Caoimhín Ó Danachair and in Lebor na Nuachongbála now known as the Book of Leinster, and then come across it apparently being *not right* in The History of Ireland by Geoffrey Keating.

And see? Now I have wildly digressed. Again. Tighermas is supposed to have been the 13th High King of Ireland

1. Tigernmas son of lofty Follach

prince over Banba of rough judgements,

seven and seventy years

in kingship over the Gáedil.2. By him were smelted, it is a tuneful fame,

https://www.ancienttexts.org/library/celtic/ctexts/lebor6.html

ornaments of gold at first in Ireland;

green, blue, purple together,

by him were put upon garments.

I am resisting, hard, the temptation to discuss the translation, this is the old Irish:

- TIGernmas mac Ollaig aird

flaith forin ̇mBanba brethgairg;

.uii. ̇mbliadna ar .lxx. dó

i rrige for Gaedeló. - Leis ro berbad is blad bind.

méin óir ar tus i nHerind;

uane gorm corcair malle

leis tucad for etaige.

http://research.ucc.ie/celt/document/G800011A#

– the important thing is “uane gorm corcair mallem leis tucad for etaige.” – uanne or uane is the old irish for green, gorm is blue and corcair is purple. So we know that the author of the Book of Leinster, or the author of the text that was copied into the book of Leinster in approximately 1140 AD or CE, whichever you prefer, felt it was utterly plausible that the colours green, blue and purple were used (together?) from the 1600s BCE for the first time.

Purple, as in Classical society, was obtained from molluscs, and this continued on for centuries. Ireland also obtained purples (and pinks) from lichens. These are a harder process than cooking vegetation to give a wide selection of yellow, so are worthy of special note. Similarly woad, the most likely source for blue in Ireland, was not a straight forward dye, not being water soluble – so has a trick before it can be used. Green is tricky to obtain as a colour straight from nature, but it is easily achievable through overdyeing processes or with the addition of Iron in the process.

“Tigernmas son of Follach took the kingship thereafter …. By him were [drinking] horns first given in Ireland. By him was gold first smelted in Ireland, and colours were put upon garments, and fringes. By him were made ornaments and brooches of gold and silver. Luchadán was the name of the wright who smelted the gold, in Foithri of Airther Life. And he was seventy and seven years in the kingship of Ireland, and he came but little short of destroying the progeny of Éber during that time. So he died in Mag Slecht, in the great Assembly thereof, with three-fourths of the men of Ireland in his company, in worship of Crom Cruaich, the king-idol of Ireland; so that there escaped thence, in that fashion, not more than one-fourth of the men of Ireland;

The fourth of the men of Ireland who escaped gave the kingship of Eochu Édgathach son of Daire Doimthech of the seed of Lugaid son of Íth. By him were made the manifold cheekerings upon the garments of Ireland—one colour in the garment of slaves, two in the garments of peasants, three in those of hirelings and fighting men, four in those of lordings, five in those of chieftains, six in those of men of learning and of poets, and seven in those of kings and of queens. From that there developed all the colours that are today in the vesture of a bishop.” https://www.ancienttexts.org/library/celtic/ctexts/lebor6.html

I am intrigued by this, but was it a thing? Did the number of colours signify rank once in Ireland? At the end of the day though it doesn’t matter, because while it is reported as a thing that Irish people did, they were supposed to have done it a millennia before common era, and as such well out of my period of interest. What it does do though is give me a definite idea that colours are, by the 12th century, numerous and well established and understood to have meaning.

I have to go do some work now, but the next avenue of research in Irish historical dyeing is looking at the incredibly common idea of the “saffron leine” – because my argument is that there is no way, at all, saffron was a commonly used dye stuff in Ireland, and the colour is descriptive of the colour and not of the source. But that’s for later.

Leave a Reply