Natural dyes have lots of issues modern dyes don’t, but they are much more fun in my opinion. You just have to approach the whole thing the way a person in period might have – what am I dyeing, how much colour do I care about, does it need to be consistent, do I need predictable results over a couple of pieces? How hard wearing does it need to be, will it vanish or turn muddy and unpleasant because I have to expose it constantly to light? Can I over dye the piece when it fades out reasonably easily? And, realistically, “can I get a nice colour from yon hedge because I’m not bringing this to town to pay of fortune for a colour I’ll then just have to mess up walking outside anyway?”

The surprising thing is an incredible amount of plants and materials will produce dye colours – the trick is to try to pick ones that will be consistent and last. If you are looking up different things to try dyeing with you are looking for words like “light fast”, “not fugitive” There is a rule of thumb out there that if a plant has a strong smell it’s probably good to dye with – but you want to be careful about working with plants you don’t know – maybe the strong smelling plant you’re working with is gently wafting poisonous fumes around your house in a twist worthy of an Agatha Christie plot?

Dyes can be classified in four categories:

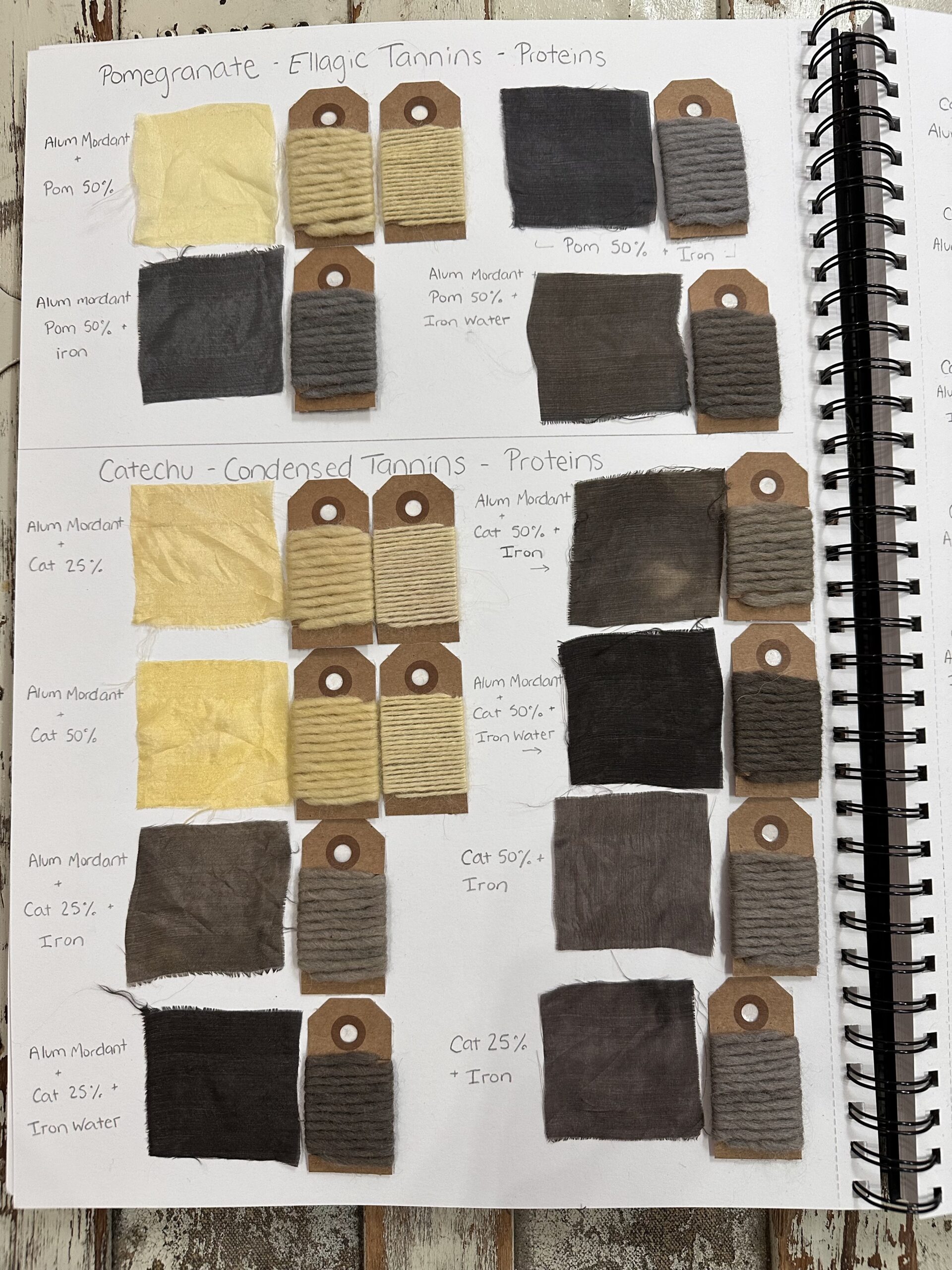

- Substantive dyes – usually dyes which are rich in tannins including barks and the leaves and fruits of trees, such as walnut, sumac, eucalyptus and oak. Substantive dyes may not require mordanting prior to dyeing, though results may still be improved.

- Adjective dyes – Most dyestuff falls into this category – these definitely need the help of a mordant in order to adhere permanently to the fiber; cochineal, and herbal/plant dyestuff

- Vat dyes – dyestuff that is not soluble in water – woad, indigo, orchil laden lichens fall into this category

- Fugitive dyes – usually from flowers, berries, spices, foodstuffs – they create nice colours that don’t last. Can be gorgeous in art projects but are not so useful for garb projects.

Most plants and flowers in nature produce yellow coloured dye – this can be changed by adding mineral salt additives (eg iron to make green) but the basic colour from nature, and most available to normal people, is yellow.

Most heavy in tannin dyestuffs (bark, nuts and so on) produce a variety of beige to brown colours, sometimes with pinks or purples when the sap is rising (birch, hawthorn)

If you want a decent blue that’s going to last you’re going to want to look into creating a woad or indigo vat. Vats come into play with your dye is hard to get out of its natural source and neither woad nor indigo are water soluble. Vats in period were an experience and a longer process than a modern indigo and hydros vat process. The gorgeous blue colours are the same though.

A lot of the fun is in overdyeing – you might not be much of a fan of blue or pink say, but dip cochineal pink yarn into an indigo vat and you may have your best purple ever.

FOR VATS – you want to dip repeatedly til the colour is about two shades deeper wet than you are hoping for dry.

Adding lots more dyestuff is actually less effective than dyeing and then redyeing your item in a fresh dyebath if you find its too pale for you.

The dyebath/vat will colour a strong colour the first time and progressively weaker colours if reused after the first. Historically the first bath would have been the most expensive, so a rich, deep scarlet would have been the first colour and cost the most, fading to a pink rinse for subsequent items that would be cheaper to pay for.

A common black dye is a result of the chemical reaction between gallotannic acid, iron and oxygen. It is also the most common way black ink was made when bound with gum.

Leave a Reply