There is a Dye house here in Ireland, AppleOak Fibreworks, who sell beautifully dyed wool and fabric as well as dye supplies to hobby dyers like me, materials and so on. It’s run from County Clare and I’ve been buying great dyestuffs from them for a while now. Last year saw the launch and beginning of their one year online Professional Natural dyers course, and I was *really, really* tempted but decided against it for last year because I’m trying to get my house renovated, but luckily Katie is doing it. It’s been great to see how she’s been getting on with it, to see her absolutely stunning portfolio grow and to get tips and tricks along the way and I am very inclined to do the course next year, finances allowing. I also was able to party crash a recent 4 day workshop at their workshop with Katie and learn LOTS about woad. (And successfully managed not to get too much drool on their stuff)

Firstly, Jennifer and Tristan Lienhard are so interesting and lovely, generous with their knowledge and experience, and have excellent ecological motivations in running their business which I admire. I wasn’t expecting the wanna be gardener to be every bit as thrilled with the course as my wanna be dyer, but as participants on the course we were helping out doing the second set of tests on 21 woad varieties, so it certainly was. I adored all of the info about the trial, inbreeding depression and hybrid vigour, how to conduct random plant testing and so on, every bit as much as the lovely morning on the fresh breezy hill looking at the patches of woad and weld, dyers chamomile, coreopsis and marigolds. It’s hard not to get carried away with my own ambitions for my dye garden, but again, house in renovation, many large vehicles making uncertain new paths on the property, general planning issues and, of course, it’s not Spring.

The purpose of the tests is to find a variety that grows well, gives as good a blue colour as possible while giving a decent yield, and also performs well in producing seed . In the mixed tests for this year the seed is not being sought, as they would be cross pollinating madly if allowed, the focus of this year was to plant samples in different patches in the slope of the hill to see how they performed in randomly assigned positions. So on our first morning we headed straight to the field to talk about and harvest our allotted, labelled, small groupings of plants. Mine were great in terms of good healthy plants, relatively pest free and lots of leaves. It was kind of amazing how attached I became to plants I was working with doing well.

The plants look somewhat like spinach and yeah, I can tell you when you’re cutting them you know they’re related to cabbages. Not horribly so or anything, but distinct and definite. The main thing about having cut the woad is that you have to start processing it quickly.

Indigo is what we’re aiming for in processing the plants, and while it is easier to obtain in quantity from other plants like Japanese Indigo (Persicaria Tinctoria), woad is close to my medieval European recreating brain. The blue colour obtained from woad plants is a mixture of indigotin and smaller quantities of other stuff, like red indirubin. And the plant also has a great deal of yellow from flavanoids, and you don’t want those, just the insoluble elements. These elements can’t be broken down with water, heat, storing or any of the usual methods we’ve talked about so far, so they usually have to be processed in a vat, as does indigo. What we have to work with in woad are two precursors to indigo proper; Indican and isatan B. I am not a chemist and I’ve been trying to work my way through a lot of papers about woad written from the Chemist’s point of view lately. I admire their work while also sometimes coming away feeling a little like my brain has been scoured out with wire wool. So forgive me if I get this wrong but I’m trying to keep it simple so that I don’t say something I shouldn’t!

so there those two are, just lurking around in the leaves not being indigo when suddenly water in large quantities gets in at them through leaf crushing, and breaks down the bonds in a process called Hydrolysis (hydro is greek for water, and lysis is ‘to unbind’). My brain is doing funny things with colour molucules bewailing how they are undone, tiny blue hands stapled to forheads under extravagant hennins… it’s a weird place in here..

Anyway, from this breakdown comes indoxyl and that’s where we will finally get our indigotin from. That’s the science. In practical terms you need to get the leaves into some water and start mushing them up quick. After that you go for chemical extraction, or squishing up all that goodness in woad balls to preserve it for later.

First off we needed to test the fresh harvest for its ability to stain blue. The first test had already been done earlier in the year so the quantity and materials were already determined. It was important to see if the plants that had done well earlier in the summer would do well again in August. So we were given our bucket of leaves with our sample number and we had to blend them down into fine leaf soup with astonishingly vivid green bubbles. As soon as possible then to start massaging/agitating a silk scarf, a small silk tester piece and a skein of wool (that was not expected to take on very much) in the fresh, green vaguely broccoli smelling goop continuously for 20 minutes without letting it surface and oxidise, Left is left over strained leaf material, right are some of the different results from this short test. Jennifer said that a higher quantity of woad would have made a stronger test colour but they had to repeat with same amount as was chosen for round one. It was absolutely fascinating seeing the range of blues and blue greens even in this short test, and as predicted the wool took practically no blue at all. The photo isn’t quite showing the blues to their best, but they were pale, as was expected from this method, with a very pleasing evenness.

It was fascinating, and more so when we started to compare the previous harvest to the current. The fear was the results would be completely different between the two tests, but the best remained the best and nothing fell down too far in their rank when comparing the results. I was very taken with French samples, even though the chinese woad (Isatis indigotica rather than Isatis Tinctoria) varieties were definitely coming out more blue, but I adored that the French seed samples produced very consistent results which I felt lined up nicely with France’s fantastic history with woad.

Next came the pigment extraction (chemical) in a large vat that could be kept at a constant temperature for many, many hours, I think it’s typically between 20 -24? It was fascinating to see the process on a much bigger scale than I would have used, but using the same, time honoured principles -steep in warm water to get the aforementioned indican and isatan into the water, when you are content everything has broken down to your satisfaction raise the PH to make the solution alkaline (soda ash and lime are both used by different people, in our case we were working with lime water) – This makes indican recombine into indoxl molecules. Then agitate the water like mad – on a small scale whisk it, or a larger scale use the agitator in the vat they had and step away or wear headphones. Whisking introduces Oxygen, which happily goes around collecting molecules of indoxyl and voila! indigo! Because it doesn’t dissolve in water each new indigo particle will saunter on down and settle on the bottom waiting to get collected when the water is gone. This gives the pigment powder that we then later use in Vats. (more on this below)

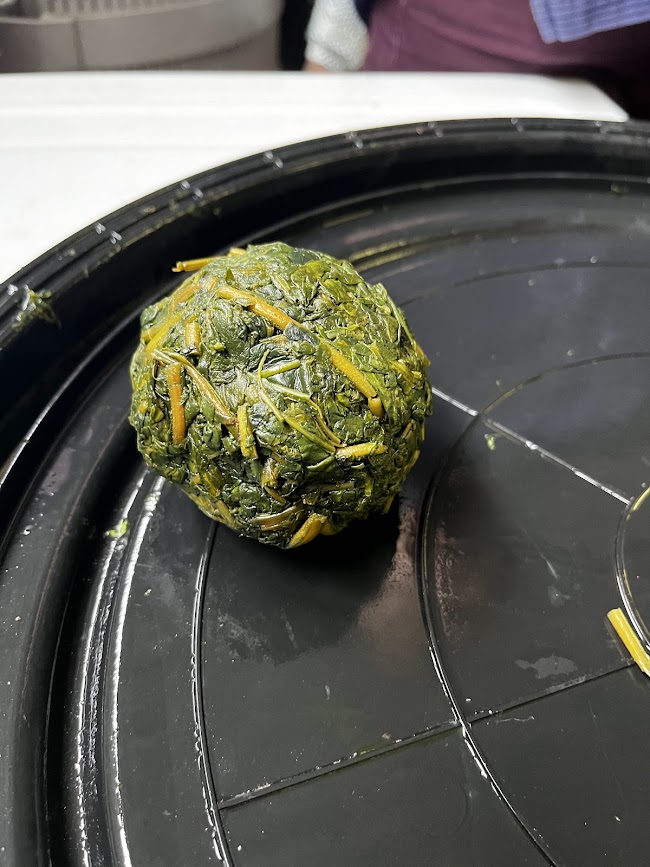

Next came stomping the buckets of woad leaves to a frothy mush with poles and then spade blades. This was tiring but pleasing work, it’s incredible the colour green that splodges around the poles. Photographs I have do not even remotely do it justice. This was done to start the process to make woad balls. I have been fascinated with the concept of woad balls since I was a kid and only barely had a notion what they were, but balls of dried leaves producing what my preteen brain had decided was ‘woooo historical magic’, what’s not to like?

Getting them into squished form quickly after harvest (for any of these processes) is key. Once they are rendered to your satisfaction, you keep them in a covered vat/bucket/vessel with a lid as close to the surface as possible and leave them to ferment. Jennifer showed us previous woad balls, one set that had been turned into balls almost immediately (top basin) and another set that were balled after I think 5 days (basket) the bottom ones were harder, denser and lighter in weight.

In ideal conditions there is almost no oxygen inside the woad ball and the bacteria Clostridium Isatidis will convert the two precursors into indoxyl. It’s an extremely historic way of preserving the indigo in a form that can be stored for later use, and extremely satisfying to make, squeezing them tightly to remove as much water as possible before drying.

Why do we need Vats when working with woad (and indigo) blue?

As mentioned above, indigo is not soluble in water. This is clearly not very good for anyone trying to get it into clothes/fabric/fibres. To make it “go” it has to be added to an alkaline solution, and then have the oxygen that made it into a collectable particle removed to release its two colour bearing indoxyl molecules. This is called reduction and we talk about making a Vat . Commonly soda ash makes the solution alkaline and spectralite or “Hydros” sodium dithionite remove the oxygen. This makes a weird yellow green solution with a dark surface that develops almost crystallinet thin slicks on top, which is known as “the flower” in dyeing communities. Now its water soluble as leuco-indigotin, a double molecule (and I’m definitely hazy on this bit so I’ll leave it at that for now.) anyway as this green yellow stuff it happily engages with fibres, and penetrates and does all the stuff you want a good dye to do. Then as you pull it, vividly green, from the vat, it takes on oxygen again, become indigo once more and stuck to the fibres. It’s like magic, and I recommend you try it at least once if you ever owned and liked a colour changing pen in your life.

So that was the woad portion of the course. It was fantastic, as was talking with all the lovely people doing the year long course and seeing their amazing portfolios and being able to discuss mordants, and ways to achieve certain effects and what the participants would love to see in the industry and the future of more sustainable, ethical dyeing in Ireland.

If you have any interest at all in Natural Dyeing, particularly on a larger scale, I would absolutely recommend you check out the course based on my 4 days of getting to tag along, the amount of information I picked up was epic, and I understand so many things that much better seeing it done on the larger scale. This is the link to more information (and I also have to say I have always had a great experience buying from them too) https://appleoakfibreworks.com/collections/1-year-professional-natural-dyers-course

Leave a Reply